An insidious myth persists even today in healthcare branding that healthcare professionals (HCPs) are emotionally detached from the brands they prescribe for their patients, relying solely on data and research to formulate their decisions. However, experience—and data!—show that physician brand loyalty often depends upon how the brands reinforce the doctor’s sense of self and personal brand of medical practice, and not just the cold, hard facts.

Most doctors would never admit to being swayed by branding perhaps because such an admission seems to threaten their sense of intelligence, as if they could be “fooled” by marketers. Let me be very clear, here. Healthcare brands don’t fool doctors. Brands aspire to be a flattering reflection of doctors’ values. No self-respecting doctor would ever select an inferior brand over a better one. Most of the time, the choice is between two or three equally good brands. If a brand doesn’t live up to its own treatment promises, then no physician would ever risk his/her reputation by prescribing it.

Perhaps doctors need to feel completely in control of their thoughts and actions, and resist the idea that there are subconscious factors in play when selecting brands for their patients. Maybe, out of tacit respect or fear of this emperor-has-no-clothes denial, this is why so many healthcare brands insist on creating brand identities that are about the product or service’s functional attributes, and not the more engaging ideas of practical and emotional benefits that dare not speak their names. As I said, doctors are only being human. Ask them (as I and many others have done) which TV shows are their favorites, and many will insist either that they don’t watch TV, or if they do, it’s 60 Minutes and cable news. Very serious stuff. However, if you ask them, say, what they think about Sawyer Fredericks winning The Voice last season, some of them might correct you by pointing out that he won two seasons ago; Jordan Smith was the winner last season. As with any living creature wary to put its vulnerability on the line, one must approach doctors in an entirely different way to account for their need to be perceived as wholly objective to anything but the facts about a brand.

When Advil and Nuprin—both identical formulations of ibuprofen—first came out, doctors recommended Advil 10-to-1 over the little, yellow “different” pill. For those old enough to remember, Advil’s brand reflected that of a doctor’s: honest, serious and progressive. Its famous tag line presented the brand as a natural evolution in pain management: first there was aspirin, then there was Tylenol, now there’s Advil. The three pills would roll out, one after the other, with Advil being the latest triumph over pain.

Nuprin, on the other hand, featured the tennis couple Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors arguing over whose pain was worse. (Turns out that Nuprin was right for both of them. Awwww.) The problem is that doctor’s and the rest of us have no empathy for celebrity pain. They don’t suffer like normal people in our minds. When doctors peered into the Nuprin brand, they didn’t see ibuprofen, they saw flash and painless stars, pandering to the serious subject of peoples’ pain. When they peered into the Advil brand, they saw themselves: responsible, clinical and effective and dutifully compassionate.

Nuprin, on the other hand, featured the tennis couple Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors arguing over whose pain was worse. (Turns out that Nuprin was right for both of them. Awwww.) The problem is that doctor’s and the rest of us have no empathy for celebrity pain. They don’t suffer like normal people in our minds. When doctors peered into the Nuprin brand, they didn’t see ibuprofen, they saw flash and painless stars, pandering to the serious subject of peoples’ pain. When they peered into the Advil brand, they saw themselves: responsible, clinical and effective and dutifully compassionate.

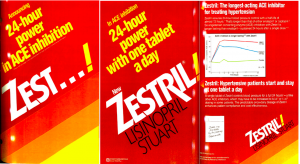

This successful emotional appeal was on display again a few years later when two brands of antihypertensive agents launched head to head. Merck developed the lisinopril molecule, an ACE inhibitor. Since Merck already had the leading ACE inhibitor on the market, Vasotec, Merck’s strategy was to license it to Stuart Pharmaceuticals (now Astra Zenenca), which had very little experience in the cardiovascular category. Merck’s theory was that Stuart would pose little threat, and Merck would have two weapons in the ACE arsenal, thereby making money off of the license while reaping the lion’s share of the lisinopril market.

Prinivil (Merck’s brand of lisinopril) launched with a quality of life campaign showing what I call the Celebration Fallacy: patients cheering about their medicine. (Has anyone actually done this in real life?)

The ads showed people summiting mountains and snorkeling in pristine waters. Zestril (Stuart’s brand of lisinopril) launched with a bold, all-graphic look, and the claim “24-hour Power.” While Vasotec, Prinivil and Zestril all could keep hypertension at bay with once daily dosing, Zestril reframed the idea into one of personal power that never quits. That is, doctor’s didn’t just see the Zestril brand as working for 24-hours; they also saw a brand that would be there for patients 24/7 just like them. Once again, by the end of year one, Zestril had 70% of the lisinopril market to Prinivil’s 30%. Zestril went on to become the best selling ACE inhibitor in the world.

Physicians may never admit being human, but examples like Advil and Zestril above continue to prove that HCPs make brand choices in the same way as non-professionals do: they seek a reflection of their own self values in the brands they use and/or advocate. It’s perfectly fine for doctors to think they have new clothes, but let’s not lie to ourselves and miss opportunities to position brands more on the emotional side of the equation rather than just nodding politely and creating branding strategies that say, “nice suit, doc.”

Thank you once again, for providing support to my ongoing harangue, I mean, discussion with clients. Here in the world of oncology, I am either told that a) Data Rules, Emotions Drool or b) The Only Emotion that Matter is Hope — wrong to both. I love to show the sales chart where oncologists used products that were contra-indicated for a specific condition — literally, the data said “THE PRODUCT IS INEFFECTIVE AND DANGEROUS” — yet the oncologist’s emotions drove them to use these products — emotions ranging from adventurous to frustrated to defiant to curious to optimistic. Oncologists will make emotional decisions independent of patient’s hope, based on their views of their reputations, practices, and themselves.

And don’t get me started on urologists….

I’m getting a lot of feedback similar to yours, Suzanne. And some of it, optimistically, is coming from clients who are beginning to realize that oncology, psychology, pain management and many other illness categories are fraught with emotional choices. This John Wayne toughness is an illusion, as my blog argues, but where are the branding strategies that pry open the doctor’s eyes like Kate Hepburn did to the Duke? Keep fighting the good fight!

“Physician brand loyalty often depends upon how the brands reinforce the doctor’s sense of self and personal brand of medical practice, and not just the cold, hard facts”.

How true. And how difficult to make some friend to believe it.