In the early ‘90s, when pharmaceutical advances in pain and inflammation were taking shape for the first time in a decade, I was working on the identity of a blockbuster Cox-II inhibitor. The company had hired a major marketing firm to conduct research and develop strategy. It cost the client around $2 million and the effort took 18 months. When they were done, they presented their findings, among which was a patient segmentation that featured 28 different segments—28 distinctly different pools of customers, they argued, that would need to be targeted in specific ways. The brand director turned to me and said: “what they hell am I supposed to do with this?”

Indeed, the information proved voluminous but inactionable. Although it is easy to fault the vendor for delivering this shock-and-awe offensive on the brand’s behalf, some of the blame lay with the client, who—out of fear of leaving no stone unturned—upended every object in the landscape in search of answers. It was at this precise moment that I vowed to create a best-in-class process designed to stop the madness so that the business of marketing could proceed without a knee-deep wade through the sludge of too much information.

First, I started with the precept that it wasn’t information we sought, but rather insights. It was not about asking every question, but rather the right questions. Second, it had to be actionable: that is, the insight had to point specifically to a finite series of strategies we could pursue. Where the shock-and-awe vendor polluted the environment with raw volume, our goal would be to distill and refine. Instead of finding the differences among 28 segments of customers, we sought to identify what one or two things they might have in common. As it turned out, a simple, qualitative exercise revealed that there was one universal insight to which all customers could relate: enduring relief. The pain category is stuck between two types of positions: those that target pain regardless of side effects, and those that target pain less ably, but spare the patient from further injury. In each case, all patients sought one central idea: sustained freedom from both exposure to pain and exposure to side effects (e.g. GI bleeds, addiction), or Enduring Relief. Our study took four weeks and cost $60,000 and, more importantly, provided a simple, actionable answer to what the brand’s identity should be about.

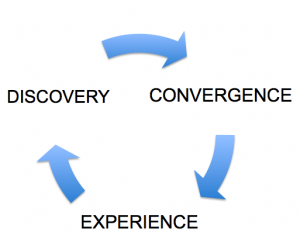

When it comes to processes—and many truths in life—the rule of three prevails: three is the simplest number of steps to create a pattern; three (as Buckminster Fuller demonstrated with his triangle-based engineering that enabled huge superdome constructions) creates the strongest shape in nature with the least amount of waste. Between too much and too little lies the Goldilocks process: a three-step process. Any process shorter than three steps is inefficient; and any process longer than three steps is incomplete. Decades of experience shows that three steps turn out to be just right.

Discovery. Consensus. Experience. These are the only three steps a best-in-class process needs. (Some argue that there should be a fourth step—Measurement—but when you think about it, this is just Discovery all over again.)