Branding a medical condition? Isn’t that the Devil’s work? Isn’t it just one more way that the pharma, biotech and device industries fool people into spending more money on their products by inventing fictional conditions? Let me tell you why this is nonsense.

We’ve written in the past about disease branding. Disease (or condition) branding, as the name implies, is not a random act or discovery, but rather the purposeful, concerted effort on the collective part of marketers, academic physicians, and doctor and patient organizations to identify and lend support and validity to health and wellness concepts. The great majority of the time, the government has no hand in the matter. Instead, condition brands generally arise out of a grassroots movement to gain greater recognition of a disease, an educational initiative on the part of healthcare groups and pharmaceutical manufacturers, or both.

Unlike with product and service branding, where identities become known almost exclusively through paid promotion, successful condition branding can only come to fruition through cooperative efforts involving pharmaceutical companies, authorities at leading academic schools of medicine (referred to in the trade as ‘thought leaders’), the entire medical community that treats patients, support societies, advocacy groups, and consumers.  Further, the effort must be coordinated with multiple communication agencies in the fields of branding, advertising, education, and public relations for the condition brand to be successfully established. Once a condition brand has reached a critical mass of recognition, it becomes self-sustaining and “owned” by society as a whole rather than by a manufacturer or special interest group. When a single party tries to create a condition brand unilaterally on its own, the usual result is a complete failure. One entity rarely speaks for every constituent.

Further, the effort must be coordinated with multiple communication agencies in the fields of branding, advertising, education, and public relations for the condition brand to be successfully established. Once a condition brand has reached a critical mass of recognition, it becomes self-sustaining and “owned” by society as a whole rather than by a manufacturer or special interest group. When a single party tries to create a condition brand unilaterally on its own, the usual result is a complete failure. One entity rarely speaks for every constituent.

Why must all parties unify around a disease brand concept? Because each constituent in the collective has a different agenda for creating a condition brand identity; and as with all identities, the goal is to find a core idea in which everyone can see a flattering reflection of these disparate agendas. Academic medical thought leaders—those in public health and/or who publish in medical journals and conduct clinical trials—want a disease brand that honors the scientific rigor of their chosen profession. Advocacy groups want a condition brand that’s considerate and relevant to their constituents. Practicing doctors and their patients are looking for a “password” that opens up a fruitful dialogue and facilitates diagnosis and treatment. And pharmaceutical companies are seeking a condition brand identity that points to their own product brands as potential remedies.

Once the decision has been made to brand or rebrand a health or medical condition identity, a best-practice model derived from past successes is the most efficient and prudent route to pursue. Here’s how a proper condition branding effort should proceed (it’s a lot like rallying votes for a bill in the US Senate):

Once the decision has been made to brand or rebrand a health or medical condition identity, a best-practice model derived from past successes is the most efficient and prudent route to pursue. Here’s how a proper condition branding effort should proceed (it’s a lot like rallying votes for a bill in the US Senate):

- A primary interested party (e.g. a patient advocacy group, physician medical society, or healthcare manufacturer with a remedy in hand or in development) takes a leadership position and creates a mission to brand or rebrand a healthcare condition that is overlooked, misunderstood, or poorly branded in the first place.

- The primary party networks with other constituencies mentioned above that are essential to creating the critical mass needed for grassroots acceptance.

- As part of the networking process, the primary party surveys each constituency to understand the outcome it seeks as part of the branding/rebranding initiative.

- A one- or two-day summit is convened with an agenda designed to align the various desired outcomes of the constituencies around a central brand identity strategy (i.e., the criteria that a condition brand name must satisfy in this particular situation). Not surprisingly, a condition branding strategy conforms to the same model as a product or service branding strategy: you collectively develop a Brand Threat (opposite of a Brand Promise) and a Brand Personality.

- Based on the consensus strategy, the collective group brainstorms and generates condition brand name candidates, and prioritizes a list of viable condition brand names.

- The brand name candidates are tested with patients and clinicians for their appeal and also to gain feedback on the pros and cons of how the names deliver on the consensus strategy.

- The summit group (or steering committee) convenes once more to review the research feedback and selects a condition brand name.

- The various constituencies then depart and begin to implement the agreed upon disease brand identity in their various media channels: member newsletters, promotion, public relations, articles and papers in well-regarded medical journals, and so on. The general public learns of this rebranded or newly branded condition identity from a variety of sources, and if the identity resonates, it takes root in our lexicon.

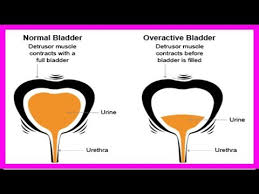

One shining example of condition branding that succeeded is Overactive Bladder, or OAB. OAB is a best-practice example of re-branding “incontinence.” All constituencies backed the concept because all constituencies were consulted when the brand name was created. Academic healthcare thought leaders respected the sobriety of losing the “bed wetting” image of incontinence in favor of a more anatomical concept. Advocacy groups were pleased that the newly branded Overactive Bladder took the stigma out of the condition for its members and blamed the problem not on a loss of personal control, but rather a faulty muscle in the bladder. (Hey, it happens to us all after awhile.)  Doctors and patients liked the discreet, simple “password” OAB, which immediately set in motion an entirely new protocol for an unembarrassed and frank discussion. And Wyeth (now part of Pfizer)—the pharmaceutical manufacturer who helped sponsor the rebranding at the time—was satisfied that the concept reinforced the mechanism of action of their brand Detrol (tolterodine) to resolve the problem. Detrol works by decreasing the “activity” of the detrusor muscle (as shown to the left) thereby enabling it to control the spasms that cause OAB. OAB was a lock that made Detrol a turnkey solution for all parties.

Doctors and patients liked the discreet, simple “password” OAB, which immediately set in motion an entirely new protocol for an unembarrassed and frank discussion. And Wyeth (now part of Pfizer)—the pharmaceutical manufacturer who helped sponsor the rebranding at the time—was satisfied that the concept reinforced the mechanism of action of their brand Detrol (tolterodine) to resolve the problem. Detrol works by decreasing the “activity” of the detrusor muscle (as shown to the left) thereby enabling it to control the spasms that cause OAB. OAB was a lock that made Detrol a turnkey solution for all parties.

It’s important to note once again that condition branding is a purposeful boon to the enlightenment of doctors, patients and the insurance entities that pay to help resolve a bona fide disease. It is not an act in and of itself to advance the agenda of any one party no matter the fear-mongering rhetoric of those who wish to profit off of scaring the citizenry with conspiracy theories. Just ask those that suffer from these conditions. They’ll tell you how real it is.