The Consolidation Blues

During my 30-year tenure with large healthcare advertising agencies and their holding companies, I have been involved in several “consolidation” pitches fielded by clients with an eye toward greater cost effectiveness. I’ve been part of the winning team, as well as part of the losing team, and I must tell you that the feeling my agency had after either outcome was exactly the same: dread. If we lost, it was dread over the prospect of business being sealed off from that particular client for quite some time. If we won, it was dread over how we would ever manage to free ourselves from the prison we had just entered willingly.

Let me explain. By “consolidation,” I mean that a large healthcare pharma or biotech client finds itself with, say, dozens of vendors across their portfolio. They regret the internal costs of managing dozens of master service agreements (MSAs), and hypothesize this: if we reduce the number of vendors to just a few, and allocate all of our brands across these few, then our internal costs would go down, and productivity would go up. As Elvis Costello sings: “It was a fine idea at the time/Now it’s a brilliant mistake.”

The roles in this dynamic have been mathematically proven in game theory, the basis of conflict resolution where each side gives up a little so that all can gain a lot. For example, say that four shepherds graze their flocks on the only fertile hill around for miles. If one shepherd starts to get greedy and increase the size of his flock to improve market share, the other shepherds follow suite. Soon, the hill becomes over-grazed, all the sheep starve and all the shepherds go broke. There should be a built-in logic for self-sacrifice for one’s own good, and the entire group should thereby thrive. (This is called The Tragedy of the Commons.)

But people are people; and since the Supreme Court of the US has determined that corporations are people too, they start to make very human errors by pursuing short-term self-interest over long-term partnership. Consolidation as it currently stands is one such game that is destined to fail by design. However, the failure is somewhat slow (about 2-3 years), so it often goes unnoticed until it’s too late (and after the original architects of the consolidation are long gone).

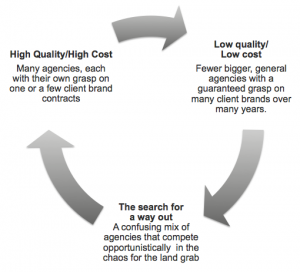

Here’s why. It is a bait and switch from both sides. Holding companies are looking for a greater share of the client’s business, as well as a predictable income stream for long-term planning. Clients are looking to reduce overhead and gain the holding company’s top talent by becoming a bigger fish in their pond. However, the winning holding company is then told that—in exchange for a greater volume of business—the holding company must reduce its billable rate by an average of 20-25%. The holding companies respond to that bait and switch with a bait and switch of their own: they remove the top talent that the client thought they were buying, and replace it with cheaper talent to recoup the 20-25% margin they just lost. The two parties become locked in a lose-lose deal that will result in great, mutual resentment over the next two to three years, after which the consolidation is dissolved in a search for the Holy Grail: higher quality at a cost that makes all sides happy.

The Agency Shuffle

When extreme consolidations fail (and they always fail), they don’t blow up; rather, they fracture and crumble for a year, leaving a big mess to clean up on both sides. Sometimes the clients conclude that the idea of consolidation is right, but the holding companies were the wrong ones. So they go through the same vicious cycle and waste another two to three years discovering that it’s the model not the players after all. Other clients go back to having dozens of ad hoc agencies as before.

There are much better ways to achieve mutual satisfaction than these two alternatives, and these are in plain sight. Healthcare companies are like one of the groups of professionals (doctors) they serve: their first goal is to do no harm. Risk-taking means doing something no one else has tried. Hence, the industry is routinely stuck with the devil they know. But consider this: clients and agencies should be more afraid of business as usual than they are of exploring other alternatives because they know from the outset that consolidations will eventually fail. And that failure costs much more time and money than exploring other areas. Is a sure failure really better than the chance at a more successful arrangement?

Dancing in the Dark

Here are some ideas for consideration that begin to shed light on a way out of the madness. Change the rules and you can effectively change the game in everyone’s favor (remember the shepherds!).

- Stop organizing consolidations around brands, and consider organizing them around functions. Clients must face up to the reality that all brands should not be managed the same way each and every time. (See my previous blog entry: HOW COOKIE-CUTTER BRAND ARCHETYPE SYSTEMS CAN LEAD TO DULL LAUNCHES) And agencies must face up to the fact that they cannot do everything and do it well. Why not assign branding to branding agencies, science to science agencies, etc. and divide the labor not by client brand, but rather across client brands? If you find the best agency to do one type of task, why not have them do that task across a range of brands? (See idea number two before you speak out.)

- Stop incentivizing agencies by how many hours it takes them to get a job done right, and consider other measures of compensation. If you pay someone by the hour and don’t expect them to drag the project out over time, you are being naïve. Cheaper talent takes longer to get a job done right. Top talent—while much more expensive by the hour—will get the job right faster and cheaper than less expensive, hourly-rate employees. Why not incentivize by deliverables? Why not incentivize by how well the agencies collaborate together on the same brand? And dis-incentivize bad behavior as well. If an agency knows that it has to get a job done right for a fixed sum, then watch how it gets done by the best people on the payroll—done right and done quickly because they stand to lose money otherwise.

- Don’t set up a system that destroys competition. Consolidation is a license to kick back for both parties. Competition brings out the best in business ventures. If you decide to consider idea number one above—organizing around brand functions and not brands—then you will need specialist agencies in branding, science, education, and campaign development. But instead of having one of each, have two or three of each and let them compete in a cost-effective way. You don’t need a dog and pony show for agencies whose capabilities you’ve already vetted. An hour pitch meeting focusing on what value each agency would bring to a particular assignment is really enough to stimulate competition without spending valuable resources on paperwork and speculative ideas that will never see the light of day.

Born to Run

One last though: holding companies have acquired agencies and other properties in the name of providing clients with more and better services. “Look,” they seem to say, “you are a big company, and you deserve a big agency. We can move the world for you.” But client satisfaction is the last thing on their agenda. Consolidation has always been about reducing competition in the market, cutting costs at the expense of customer satisfaction, and passing the savings on to their own CEOs and shareholders. Bigger is not necessarily better in the idea business. You don’t need dozens of agencies and you don’t need fewer agencies, you need a handful of the right kinds of agencies to address the tasks at hand (not necessarily the brands at hand). Choose based on the type of work to be done, not the volume. And once you’ve found the right agency partners, don’t try and squeeze them unreasonably. A healthy respect among partners will gain you more than your money’s worth. No one has ever cost-cut their way to success in the service of customers.