People’s behaviors and buying preferences change significantly when seeking a remedy for an illness that affects them. They go from being “consumers” of goods that celebrate their sense of self–“I got a new iPhone!” “A new Dior bag!” “A new Mustang!”–to a compromised and diminished version of themselves. Healthcare brands are products that people don’t want to buy, but rather need to. As such, they are more about a protection of self, a desire to restore normalcy as quickly and discreetly as possible, even if it means over-medicating and suffering the consequences of increased side effects (“It says two Advil on the label; I’ll take four”). No one wants to proclaim, “I got Zovirax and my cold sore went away!” While this is a topic of great richness to explore, I wish to turn my attention to a different set of beliefs and behaviors. When people become caregivers for others, their own need to define their aspirational selves trumps what may be good for the patient.

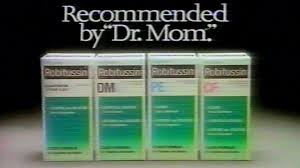

Let’s use a very familiar example. While contemporary trends are shifting a little from mothers to fathers in the family dynamic, it is still the woman’s role to be the primary caregiver for the family. Whitehall-Robins, the division of Wyeth (before it was acquired by—here they come again—Pfizer), very astutely branded their flagship cough brand, Robitussin, with the woman-as-primary-caregiver in mind. Robitussin, and its sister product, Robitussin DM, contain guaifenesin and dextromethorphan respectively, two drugs approved in the 1950s. Very safe and effective. The first is a mucolytic (breaks up mucus and phlegm) and the second a cough suppressant. If you examine the ingredients in dozens of OTC cough medications, one or both of these drugs is/are in them all. So how did Whitehall-Robins create a unique brand? By following a branding best practice: take a value esteemed by customers, and transfer it to the brand. When it comes to keeping the family healthy, mothers have the same self values as doctors: first, do no harm; and second, go with your most reliable remedy. Illness in children is no case to get fancy and take chances. The brilliant result was branding Robitussin as “Recommended by Dr. Mom.”

When’s she at home, everybody else is in her office, and she’s the doctor. Now if Mom gets sick, she may take a swig of knockout Nyquil, or pop a Mucinex (the exact same ingredient as Robitussin, but branded as a “powerhouse” force against evil mucus). However, as Dr. Mom, going with a brand proven over a half century to be effective and gentle reinforces her image as a responsible caregiver. She wants her own cough to go away fast, and treats aggressively. But for her “patients,” her pride in not causing additional harm trumps her desire to treat aggressively. This is normal behavior in a caregiver mindset.

Perhaps the best example of this mindset can be seen in the hysterical (as in crazy, not funny) movement not to vaccinate young children. Every government health authority and practicing physician that I know or have met considers vaccination to be one of the greatest accomplishments of modern medicine. Due to vaccination, the world avoids the following (a very small sample):

- A 1,900% increase in polio

- 2.7 million measles deaths per year

- A whooping cough (pertussis) epidemic that could cause pneumonia and lead to brain damage, seizures, and mental retardation

- A rubella epidemic, resulting in heart defects, cataracts, mental retardation and deafness

- A 600% increase in lifelong Hepatitis B infection, resulting in a 25% death rate from liver disease.

I could go on, but it wouldn’t matter to about 10% of the parents in the United States who do not vaccinate their children. There are a number of “reasons” (all taken from research I’ve done over the years):

- Religious objections (leave it in God’s hands, like the Amish)

- Old diseases, like diphtheria and polio, don’t exist anymore, so why vaccinate?

- Since most children are already vaccinated, it’s no big deal if a few kids aren’t (Fact: at least 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated for the disease to be effectively wiped out; the US is currently at 90%)

- Chicken pox is a mild disease, so my child doesn’t need the vaccine (Fact: even with vaccines, chickenpox causes more deaths than any other vaccine-preventable childhood disease—one child a week currently)

- Good nutrition and natural remedies offer enough protection against disease, so vaccines aren’t necessary (as if it were a nutritional issue!)

- Why bother? The vaccine immunity wears out over time (Why eat? You’ll just be hungry later)

- It’s too much of a hassle to go to the doctor and remember the appointments.

I’ll resist the further temptation to refute any of this nonsense because it detracts from my central point here about how a caregiver mindset affects buying decisions in healthcare. Besides, healthcare transactions are not much different than consumer goods purchases when it comes to the stupidity of many people. Foolishness is too unpredictable to model by even the most expert marketers. My point is best made by the two reasons that many educated parents give about why they don’t vaccinate their children:

- Vaccines can cause serious problems (autism, SIDs) or even cause the very illnesses they are trying to prevent; and

- Giving a child multiple vaccinations for different diseases at the same time increases the risk of harmful side effects and overloads the immune system.

The origin of these incorrect claims can be traced to a very reputable publication, the British medical journal, The Lancet. In 1998, Dr. Andrew Wakefield, a surgeon and medical researcher at the time (he has since had his license revoked by the British General Medical Council), published a study of 12 children, each of whom received a single vaccination to prevent three diseases: measles, mumps and rubella (MMR). He found that three of his research subjects became autistic, and therefore attributed the autism to the vaccines. These are the facts:

• no other researchers have ever been able to duplicate his findings,

• standard research trials on vaccines are done with tens of thousands of babies (not 12), and

• Dr. Wakefield excluded other medical criteria that could account for the autism,

• he was apparently found to have some type of vested financial interest in the outcome.

The whole business is a sordid one. The Lancet withdrew the article from its archives.

Despite all evidence to the contrary, a good number of the anti-vaccine movement still firmly believes Dr. Wakefield’s study to be valid. Jennie McCarthy, a television personality and 1993 Playboy Playmate of the Year, most famously raised the volume on Dr. Wakefield’s debunked findings. Using her fame as a pulpit, and her own experience as a mother with an autistic child, she has put a spotlight on the matter that just won’t shut off. Which brings me to my point: why would a caregiver defy all logic in favor of a subjective choice to avoid a healthcare purchase for those in his/her care? As with the Robitussin example, the reason is that fear and guilt about potentially causing harm trumps the facts, even though the odds are all but guaranteed in the caregiver’s favor.

A research exercise done in 1994 by Dr. David A. Asch, Professor at the Perelman School of Medicine, offers one of the most cogent portraits of caregiver values on the subject of vaccination. He posed the following scenario to a group of parents:

- There is a flu epidemic that can be fatal to children three years of age and under

- There is a vaccine that is guaranteed to prevent any child against the flu

- Out of every 10,000 children who DO get the vaccine, five will die

- Out of every 10,000 children who DO NOT get the vaccine, 10 will die.

Even though not getting the vaccine puts one’s child at twice the risk of death, many parents said that the guilt over their actions outweighed letting the chips fall where they may from their inactions. In other words, they would rather put their child at greater risk of death than take the chance on feeling responsible for their death as a result of something they did. Stipulating once again that vaccination should be a no brainer, it is plain to see why some caregivers opt out of the choice to act. And aside from any moral or intellectual judgments, the key takeaway is that the presence of illness in life alters the way that people relate to brands, especially healthcare brands. Additionally, when someone acts as a caregiver, their fears about causing harm–vs. preventing or treating it–often compel them to throw the facts out the window, cross their fingers and hope that they can beat the odds. The real thing being denied by the anti-vaccine movement is their selfishness in putting their own vulnerability ahead of their child’s.